The Checker Maven

The World's Most Widely Read Checkers and Draughts Publication

Bob Newell, Editor-in-Chief

Published each Saturday morning in Honolulu, Hawai`i

Contests in Progress:

A January Warmup

In many parts of the Northern Hemisphere, January is a cold month, and so a warmup might be just the thing! Here is a simple problem to get you started with this month's Checker Maven challenges--- but beware, they all won't be this easy!

Brian Hinkle sent us this run-up from the Double Corner opening:

| 9-14 | 23-18 |

| 14x23 | 27x18 |

| 12-16 | 22-17---A |

| 16-19 | 24x15 |

| 10x19 | 31-27?---B |

A---A defense from Teschelheit's Master Play of the Checkerboard, unfortunately unsound.

B---Loses at once, although White is probably already lost. One alternative line of play from the KingsRow computer engine is this: 26-23 19x26 30x23 11-15 18x11 8x15 32-27 5-9 31-26 4-8 25-22 8-11 23-18 15-19 27-23 11-16 17-13 7-11 29-25 1-5 22-17 3-8 17-14 8-12 25-22 11-15 18x11 9x27 Black Wins.

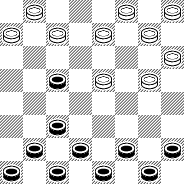

After 31-27, the following position arises:

How quickly can you solve this one? Click on Read More for the solution - but give it a good try first.![]()

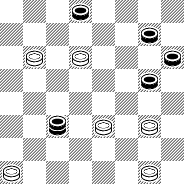

Can You Be The Third Person In The World To Solve This?

an original problem by contributing author Brian Hinkle

Only 2 players in the world have solved this 6x5 puzzle! Can you become the 3rd person to solve it?

So far only Alex Moiseyev and Jim Morrison could solve it.

On a scale of 1 to 10 (with 10 being the most difficult) Alex gave it a 7, and Jim gave it an 8.5. Both enjoyed it thoroughly.

Gerry Lopez, Leo Levitt, Carl Reno and many others have all failed to solve it - even with computer help! A number of players simply thought it was set up wrong!

The solution will be published online here in The Checker Maven on May 7, 2005.

Please send any human (no computers answers please!) solution to:

How hard is this puzzle? Cast your vote here.

February 1, 2005 update: solved by Albert Tucker! Will you be the next one to crack this toughie?

The Challenge of Checker Problems

That brings up the question that is often heard about checkers being "dead." The best computer programs today are at an extraordinarily advanced level, very likely beyond the best human players. Computer programs were always relatively good in checker tactics; but now, with enormous opening databases of half a million to a million positions, endgame databases which comprehensively solve endgames of up to 10 pieces, computer programs seem to know just about everything about checkers. The University of Calgary has as its goal the complete "solution" of checkers, and they think they will do this in the next few years. We believe that they will, in fact, accomplish this feat.

But does the fact that a "solution" for checkers exists (or will exist) mean that the game is "dead"? We think that is only true if you are playing against the world-class computer programs that know the "solution." In a game between humans, especially an over the board game, checkers is not and will never be "solved." There is too much challenge and enjoyment in the game as played by mere mortals.

What has this got to do with checker problems? It's simply that these problems, especially the better and more clever or entertaining ones, show the depth of the game. Struggle with a couple of these gems and you'll see what we mean. You'll find that there's a lot left for you personally in the grand old game. Visit Jim Loy's site and start with his beginner's problems. You'll quickly understand.

The Checker Maven is produced at editorial offices in Honolulu, Hawai`i, as a completely non-commercial public service from which no profit is obtained or sought. Original material is Copyright © 2004-2025 Avi Gobbler Publishing. Other material is the property of the respective owners. Information presented on this site is offered as-is, at no cost, and bears no express or implied warranty as to accuracy or usability. You agree that you use such information entirely at your own risk. No liabilities of any kind under any legal theory whatsoever are accepted. The Checker Maven is dedicated to the memory of Mr. Bob Newell, Sr.