The Checker Maven

The World's Most Widely Read Checkers and Draughts Publication

Bob Newell, Editor-in-Chief

Published each Saturday morning in Honolulu, Hawai`i

Contests in Progress:

Fundamentals

One thing experts agree on: if you're going to master something, whether it's playing baseball, writing novels, or becoming a checker champion, you've got to know the fundamentals. In the photo above, an aspiring baseball player is learning the fundamental skill of making contact with the ball.

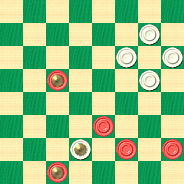

Our game of checkers has its own fundamental skills, and solving a position like the one below is a definite and required step on the road to excellence.

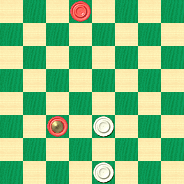

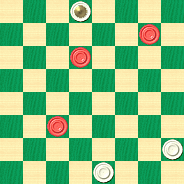

WHITE

White to Play and Draw

W:W23,31:B2,K22.

The Post-Holiday Blahs

The holidays have speeded by and North America is in the depth of winter. Even here in Waikiki, temperatures drop at night and sometimes get as low as 60F (no, we don't expect much sympathy).

Don't get the post-holiday blahs. Tackling a checkers speed problem will keep the blues away. And to ensure that the desired effect is achieved, we're putting forth a very easy problem. So easy, in fact, that we think you can solve it in a couple of seconds. But, generous as we always are, we'll give you extra time--- a full five seconds, in fact!

Click on the link below to show the problem and start the clock. Think fast!

January 2013 Speed Problem (very easy, 5 seconds)

When you're done, come back and click on Read More to see the solution.![]()

The New Year 2013

Another new year is just around the corner, and The Checker Maven hopes that it will bring you everything that you might wish for. For our part, we intend to bring you another year of checker enjoyment. Let's close out this year with a problem that's relatively easy and with a lot of practical, over the board application.

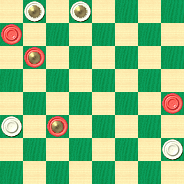

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W28,21,K2,K1:BK22,20,K9,5.

Solving this one won't take you as long as some others, but you'll appreciate the clever way in which a basic principle is applied. Give it your best and close out 2012 in style. Clicking on Read More will show you the solution as always. Some things don't change from year to year!![]()

Deficit Spending

Bill Salot's amazing series of problem composition contests continues. Bill reports receiving enough problem submittals to keep the contest running for quite some time to come. To view, try out, and vote on the latest problem entries, click the link in the left column marked Compositions.

As an example, here's one that's running now called (rather appropriately these days) Deficit Spending.

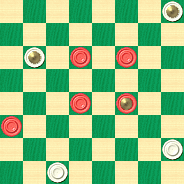

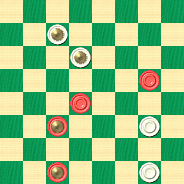

WHITE

White to Play and Draw

W:WK4,K9,28,30:B10,11,18,K19,21.

For the solution and many more fine problems, check out the website.![]()

Holidays 2012

The Checker Maven wishes all our readers the best of the holiday season. No matter what holidays you celebrate and how you celebrate them, checkers is our common bond, and for your holiday enjoyment, we have an unusual problem to present.

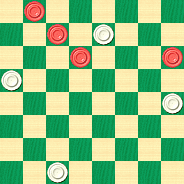

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W30,20,13,7:B12,10,6,1.

What makes this problem unusual? We'll give you a huge hint: Moves that you might make almost automatically won't be right.

Solve the problem, check the solution by clicking on Read More, and enjoy the season!![]()

Thanksgiving 2012

Thanksgiving, our favorite all-American holiday, is soon upon us, and we hope you enjoy the celebration as much as we do. Family dinners, such as the one shown above, are a holiday tradition. Can you recognize the family in the photo?

As usual at this time of year, we turn to our favorite all-American checker problemist, Tom Wiswell, for today's selection.

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:W25,22,21,17,K7:BK19,10,6,5,K3.

Add a few moments of checker enjoyment to your holiday. Solve the problem after your main course and before dessert. Then have a second helping of turkey and a slice of pumpkin pie. Mr. Wiswell describes this problem as "more amusing than difficult." While it requires precise play, it certainly isn't as difficult as some of his others.

When you've found your solution, click on Read More to verify your moves.![]()

Really Easy

Some problems definitely fall in the "really easy" category; they're as simple as two plus two equals ... how much was that again? Oh, right, four--- in any integer arithmetic of base five or higher, to be a little more precise. (One could argue that two plus two equals four even in arithmetics of base four or base three, but the symbol "4" wouldn't exist. And in base two, the symbol "2" wouldn't even exist. We'll stop there!)

In checker terms, today's speed problem is also really easy even if it's a cut above the trivial. You won't need much time for this one; ten seconds is way too long but because of our innate generosity, we'll give you ten seconds anyhow.

When you're ready, click on the link below, solve the problem, then come back and click on Read More to check your solution.

November Speed Problem (very easy)

![]()

The Deckhand

The deckhand in the photo above appears to be contemplating some sort of difficult shipboard task, and she doesn't appear too anxious to get about her business. Can't say that we blame her; some pretty heavy work happens on a commercial sailing vessel.

We're sure, though, that you won't have similar reluctance in tackling today's checker problem, which was composed by Chris Nelson, who used the nom-de-plume of "The Deckhand." We don't know why Mr. Nelson, who was a denizen of Brooklyn, chose this pseudonym. Perhaps he was a spare-time sailor. But we can say for sure that he was a fine checker problem composer, as the offering below will handily demonstrate.

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:WK6,K10,24,32:B16,18,K22,K30.

Get on board and solve this problem. It may not be as hard as shipboard labor, but it presents a nice little challenge. Then sail your mouse over to Read More to see the solution.![]()

One Stroke

The item shown above is called a "one-stroke" brush, intended for use with the "FolkArt One Stroke" painting technique. Though we know very little about this brush technique, it certainly sounds fascinating.

We've never claimed to know a lot about our game of checkers, either, but today we present "one" stroke problem, and solving it it will call into play the technique of checker visualization, which we believe to be a fascinating art form in its own right.

WHITE

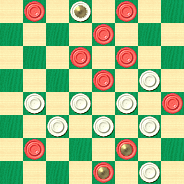

White to Play and Win

W:W32,24,23,22,19,18,17,16,K2:BK31,K27,25,20,15,11,10,7,3,1.

Now that's "one" stroke problem! Try to solve it without moving the pieces; when you've had your brush with this one, sweep your mouse to Read More to see the solution.![]()

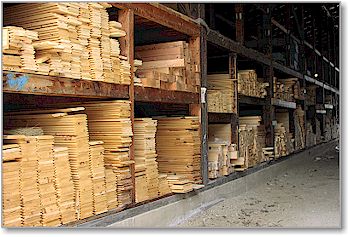

Three by Three

Everyone's heard of a two by four (2x4), and there are other familiar sizes, such as 1x4 and the larger 4x4. But have you ever heard of a three by three (3x3)? There is such a thing, and in the strange world of "dimensional lumber" a 3x3 is in reality 2.5 inches by 2.5 inches.

Fortunately, there's no such thing as "dimensional checkers." A 2x2 or a 4x4 ending is just what the label implies. (We're not really sure where half a checker piece would fit in the scheme of things!) Today, we'll look at the 3x3 ending that's diagrammed below. It's from a game played over the board many years ago at a club in the St. Paul, Minnesota area.

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:W31,28,K2:B22,10,8.

Don't get cut down to size; sharpen your wits, not your saw, and see if you can solve the problem. When you have the answer, buzz your mouse on Read More to see the solution.![]()

The Checker Maven is produced at editorial offices in Honolulu, Hawai`i, as a completely non-commercial public service from which no profit is obtained or sought. Original material is Copyright © 2004-2025 Avi Gobbler Publishing. Other material is the property of the respective owners. Information presented on this site is offered as-is, at no cost, and bears no express or implied warranty as to accuracy or usability. You agree that you use such information entirely at your own risk. No liabilities of any kind under any legal theory whatsoever are accepted. The Checker Maven is dedicated to the memory of Mr. Bob Newell, Sr.