The Checker Maven

Jump to navigationWe Got Problems

In regular life, problems are, well, a problem, and we don't want too many of them. But in the game of checkers, it's another story altogether.

In our ongoing Checker School series we've often stressed the importance of solving checker problems. But you don't need to just take our word for it. The following interesting passage appears in Andrew J. Banks' eclectic book, Checker Board Strategy. The author is Willie Gardner, a reknowned player and analyst from days past, and was first seen in the publication North American Checker Board.

Problem Solving

Problem solving is, in my opinion, the real science of draughts playing. In the study of problems one finds the greatest pleasure that the game affords, and at the same time insensibly imbibes all the requisites, analytical and constructive, that make the draughts player.

The study of the openings takes a second place in the education of the student. It is beneficial to the extent that the student may learn in an hour, from a compiled analysis of any opening, such traps and snares to avoid as would take him months, or probably years, to find unaided. However, in what position is the student who has crammed his head full of Sturges', Bowen's and Janvier's compilations, but has neglected the endings, when he finds himself with the winning side of First, Second, Third and other positions of the sort, and unable to effect the win? Such a player is celebrated for his great knowledge of the book; he is on a high pinnacle of fame, and the fall in his case is tremendous, sometimes greater than he can recover from. To play draughts well, and to find real pleasure in the game, I advise problems.

Sturges' collection is, perhaps, the best to begin with, and Gould's Book of Problems. Those with about four pieces on a side are my own especial favorites---long winded affairs, evolving the science of end-play. The two-to-two catch problems, though often brilliant, very rarely occur in play, hence their educational value is not so great. As to the crammer, what pleasure has he, with his mighty and extensive knowledge of every possible variation, when playing a game? He is simply automatic, if his opponent play so and so he knows the book reply, and there he sits, waiting for the other fellow to fall into some cut and dried loss, when he emits a mirthless chuckle, and remarks, so and so shows that to be a loss.

If the other fellow, however, gets off the beaten path, and wins, then Mr. Bookman cries, "I never saw that before! Where can I get some play on it?" Problem work is required throughout the game of draughts; its aid is required to win, and by its aid many an apparently hopeless game can be saved. Often I have heard the remark anent an old noted problemist, one of England's finest players in his day, that he never knew when he was beaten.

The end game student evolves from his every day practice his own natural systems of opening; this is the system that, I believe, brought forth the three greatest players the world has yet seen---Anderson, Wyllie, and Martins.

Willie Gardner

Interesting advice, and in accord with Grandmaster Alex Moiseyev's advice, "No opening books for the first thousand games!"

So let's solve a problem taken from Mr. Banks' book (he did not list the composer). This one is extremely easy.

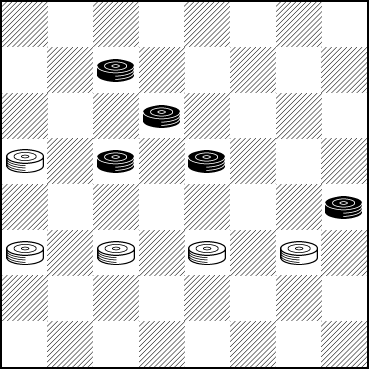

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:B6,10,14,15,20:W13,21,22,23,24

How about one that's a little bit harder? This is from the same book and is attributed to Willie Ryan.

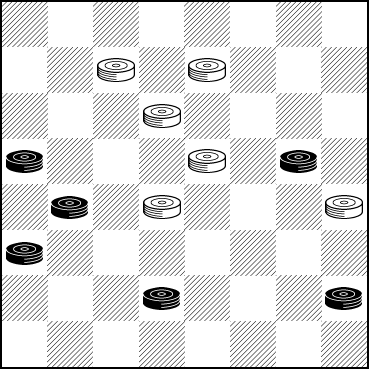

BLACK

Black to Play and Win

B:B5,7,12,16,17,20:W13,15,18,23,26,27

The problems are clearly at the beginner level, but as usual we invite more advanced players to see if they can solve them at a glance. Players of any level will of course have "no problem" clicking on Read More to see the solutions.![]()

Solution

First problem:

24-19 15x24 22-18 White Wins. Easy!

Second problem:

5-9 13x6 7-10 15-11 10-15 18-14 15-18 14-10 (or just about anything else) 18-22 Black Wins. Not so tough after all.

As we've said before, if only life's problems were so easily solved!

You can email the Webmaster with comments on this article.