The Checker Maven

Jump to navigation50th Problem Composing Contest

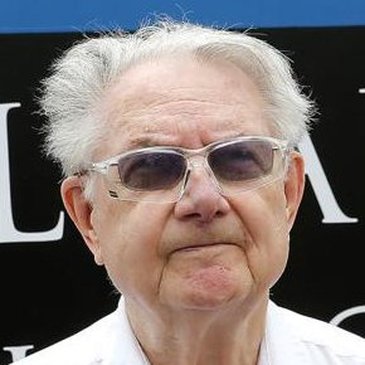

Mr. Bill Salot

Today (March 21, 2020) marks the start of Bill Salot's 50th Unofficial World Championship Checker Problem Composing Contest, which can be found on the American Checker Federation website.

Mr. Salot has long been an inspiration to us (and is indirectly responsible for our decision to continue publishing The Checker Maven beyond our initial 15 year run). He has reached age 90 without skipping a beat or seeming to slow down in the slightest.

Mr. Salot's eight-year long series of competitions has brought us a wealth of modern checker problems of amazing depth and quality. Each contest is eagerly anticipated by solvers and composers alike. Mr. Salot was kind enough to grant us an interview on the occasion of this milestone 50th event.

What gave you the idea for these contests in the first place?

It developed over a long period of time.

During my teen age years, in the 1940s in Detroit, I learned that tournament play was hard work while composing problems was fun. The latter became my primary hobby.

By the 1960s, I was corresponding with great composers. We freely shared many original problems, and published our best in the checker journals of the day. Occasionally our problems appeared side-by-side, and I found myself comparing them to determine which impressed me most.

I passed on to my composer correspondents the idea of side-by-side competition, and they liked it. A series of contests was born. We composers agreed to my publishing small groups of our confidential, original, unpublished problems along with requests for readers to rank the problems and mail me the results for publication.

Most , if not all, of the judges in a given contest ended up being the composers who did not happen to have a problem in that contest. They rotated between competing and judging. They included Ben Boland, Tom Wiswell, Joe Charles, Saul Cass, Milton Johnson, Floyd Brown, a young Melvyn Green, and others.

There were more than 30 such contests in the late 1960s and early 1970s. You can find them recorded in the ACF Bulletin and Elam's Checker Board, a few in the English Draughts Journal and a New Zealand publication.

The contests died out partly because of composer burnout and partly as a result of my parents' illnesses, together with a change in my responsibilities at work. I then dropped out of checkers for more than 35 years.

I woke up when a friend told me that nowadays chess and checkers are played on the internet. He gave me a couple of web sites. On the front page of the ACF site, previously published problems were periodically displayed. I thought, what a fine place that would be for a composer to display original, unpublished problems!

Later somebody posted, on the ACF Forum, a survey question complete with means to cast electronic votes. I saw that would be a great tool for reviving problem composing contests. Eventually Jason Solan set up a contest page and taught me how to administer it. The first contest then took place in January 2012.

How would you describe or characterize the way the contests have been received by the checker community? What sort of feedback have you gotten?

The number of returning visitors to and participants in each contest probably rivals the number of visitors and participants in most checker forums. In my infrequent ventures into tournaments, I get unsolicited positive comments and encouragement, never anything negative. The same is true for voting correspondents. So I would say the contests are generally well received by the checker community.

But composers tend to be more critical. They dislike problems that may be similar to published play, or seem undeserving of the votes they received, or are too unnatural in appearance, or too simple, or too laborious. Composers are sometimes sensitive to how problems are selected, or how solutions are presented, or how slow the contests are, or how few participate. I think all these criticisms are constructive, and the contests have improved as a result of them. I believe competing composers are generally loyal, have compositions to spare, want to win, and when they persist, eventually do win, while generally accepting losses along the way.

What do you see for the future of these contests? Do you plan to continue them indefinitely?

Yes, certainly continue them indefinitely! The backlog of original, unpublished problems has not run out. The contests should have some time left. After all, I am only 90. But eventually they will cease, unless and until somebody else wants to give them a try. So far there have been no applicants.

Problem composition is a true art. Have you seen this art develop over the course of the first 49 contests? How would you characterize today's problems compared with past history?

Problemists feel like artists, even when not recognized as such. But isnít that true of any avocation? Yes, the quality of the contests themselves have continuously improved, thanks to preliminary reviews, private discussions, computer-driven enhancements, and old-fashioned competitiveness. I canít emphasize enough the powerful influence of computers on todayís problems. They not only catch unsound analysis, they spring incredible surprises that seed new problems, many of which should be at least partially credited to the computer. The computer is the difference between historyís unsurpassed gems and masterpieces versus todayís new twists that would not exist without the computer. The computer is to problem composing what fracking is to natural gas production.

Any further thoughts or comments? Any stats you'd like to share?

Statistics are a boring waste of time unless they tell you something you didn't know before. Many stats on past problem contests (2012 - 2019) are posted at the web site. They are also in the annual Year in Review" articles on the ACF Forum.

Let me mention a few things that the contest statistics have taught me, or I should say humbled me.

1. One well-known player warned that the problem composing contests would not get off the ground, if previously published and flawed problems were not screened out beforehand by reviewers with huge databases. He was right. The first year, 7 of 30 problems entered (>23%) were disqualified, including the winners of 2 contests. A call went out for willing reviewers with large databases. A team was formed that is still intact. Only one problem was disqualified in 2013, one in 2014, one in 2016, one in 2017, and two in 2018. So 6 of 191 problems entered after 2012 (<3.2%) were disqualified. Thatís not perfect, but not bad.

2. Another well-known player recommended that the contests not include problems that were 4x4 or smaller. He warned that almost all ideas possible in positions that small have already been published. He apparently was mistaken. Of the 215 problems not disqualified in Contests 1 through 48, 66 (>30%) were 4x4 or smaller. Contest 10 was devoted entirely to 4x4s; Contests 40 and 50 have only 3x3s. Such problems apparently are not exhausted.

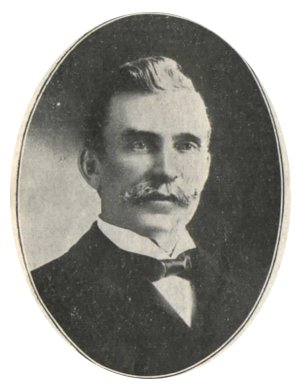

George H. Slocum

3. These contests included perhaps the rarest of all human competitions, the living versus the dead. Six times, living problemists were challenged by George H. Slocum, who died in 1914. Slocum is acknowledged as one of the greatest checker problem composers of all time. Jim Loy found a bunch of Slocum problems published in an obscure journal, unknown to our generation because they were never republished elsewhere. We entered six of them in contests, during 2016-2017, to see how they would fare against todayís talent. They all lost, which only means they probably were not among Slocumís best efforts. After the votes were counted, each of the six Slocum problems was disqualified due to their prior publication. These problems and disqualifications were not counted in item 1 above.

4. The three contests with the most votes by far were contests 2 (35 votes) and 3 (40 votes). They made us think that the contests had exploded in popularity. But that didnít make any sense. Those early contests had no publicity outside of the web site, and they did not run for six weeks as they do now. It turned out that a strange glitch in the voting program was resetting the voting button, implying that a vote was not accepted and needed to be cast again. The Web Master was unable to eliminate the glitch, but he did add an ďI already votedĒ button, which persuaded voters to not vote multiple times. After that, the voting settled into a normal average of 17 per contest.

5. After years of problem composing experience and correspondence with many great composers of yesteryear, I truly expected to dominate these contests at the outset. That was before I heard of the likes of Roy Little, who subsequently won or tied for first 19 times and won Problemist of the Year 4 times, and Ed Atkinson, who won or tied for first 14 times and won Problemist of the Year 3 times. They did it all without entering every contest. I am the only one who did. In contests that Roy and Ed entered, Jim Loy and I each won or tied for first only 7 times. Leo Springer did it 5 times in 5 tries. The sum of all those wins exceeds the number of contests because of the many ties. I am especially humbled by my 6 entries that received zero votes each.

6. I believe some of the clearest indications of the contest voting statistics apply to other aspects of human life, such as politics, religion, ethics, morals, etc. Different people simply look at the same problem and see something entirely different. They often, not just sometimes, draw diametrically opposite conclusions. In 32 of the first 48 contests, every problem received at least one vote for first place. In other words, two-thirds of the time, every problem, even the worst one, is voted best by somebody. If we cannot agree on the value of something as minor as a position on a checkerboard, is it any wonder that we canít consistently agree on real world issues?

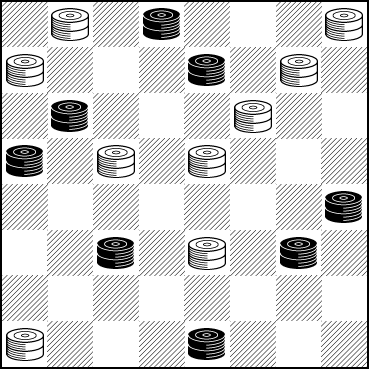

The Checker Maven once again thanks Mr. Salot for his time in providing answers to our questions, and for the opportunity to give our readers an insight into his monumental, ongoing contributions to the game. Now, as a special treat (and it's special even if you've seen it before), here is a unique problem by Bill Salot, which he originally called Don't Ask--- as in, "don't ask" how the position arose!

WHITE

White to Play and Win

W:WK1,K4,K5,K8,K11,K14,K15,K23,K29:BK2,K7,K9,K13,K20,K22,K24,K31

This one is really something, and we're certain you'll enjoy solving it. But if you're not able to contest it, clicking on Read More will uncontestedly show you the solution.![]()

Solution

Problem, solution, and notes A through D by Bill Salot.

23-27 9x18---A 27-32 7x16 8-12 18x11 12x28 White Wins---E

A---7-16 (arguably a better defense), *15-18---B,C 22-15 *8 12, 9-18 12 28, 31-24 28 19 White Wins.

B---(off A) Not 14-18 (loses), *22-25 5-14 (order of jumps immaterial) *16-19 29-22 19-26 Black Wins.

C---(off A) Not 8-12 (only draws) 9-11 12-28 31-24 28-19 *2-6---D 1-10, *11-15 Drawn.

D---(off C) Not 22-26 (loses) *19-15 11-18 *1-6 2-9 5-30 White Wins.

E---No matter what Black does, short of just giving up a piece right away, White has a two for one and a win.

1) 2-7 5-9 13-6 1-3

2) 11-7 5-9 13-6 1-3

3) 11-15 5-9 13-6 1-19

4) 11-16 32-27 31-24 28-12

5) 13-17 1-6 2-9 5-21

6) 20-16 32-27 31-24 28-12

7) 22-17 1-6 2-9 5-21

8) 22-18 28-24 20-27 32-14

9) 22-26 28-24 20-27 32-30

10) 31-26 28-24 20-27 32-30

Correspondent Brian Hinkle points out that this is surely a record, unlikely to ever be surpassed, with no less than 10 two-for-one shots in a single checker position. If anyone can compose a problem that has more than 10 at a single juncture, we'd all like to know!

We hope you enjoyed this visit with Mr. Salot and encourage you to give yourself a real checker treat by participating in his contests, whether as a solver or a composer.

You can email the Webmaster with comments on this article.